WAR IN

EUROPE

In August 1914, after decades of tension between the Great Powers of Great Britain, France, Germany, Russia, and Austria-Hungary, the European Continent finally exploded into all-out war. Following rapid advances by the German Army in August 1914, a stalemate developed as both sides dug in.

Over the next two and a half years, the horrors of modern warfare became visible for all to witness as 19th-century tactics of massed infantry charges collided with 20th-century technologies such as the machine gun and poison gas. Across the Atlantic, the United States remained wary of becoming involved in a European conflict. Global events finally drew America reluctantly into a world war.

WAR IN EUROPE:

FEATURED SECTIONS

In 1916, Woodrow Wilson campaigned for reelection on a platform of continued neutrality. This postcard features a photograph of President Wilson atop a message of friendship and goodwill towards Germany.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1969.66.1496

Six months after winning reelection, Wilson went before Congress to ask for a declaration of war against Germany.

KEY EVENTS LEADING TO

AMERICAN INVOLVEMENT

In June 1914, Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by a Serbian Nationalist in Sarajevo. The death of the heir to the Austrian throne set in motion a series of alliances that drew the entire continent into war. Austria-Hungary blamed Serbia for the assassination and declared war on July 28. In response, Serbia’s ally, Russia, declared war on Austria-Hungary. One by one, the nations of Europe were drawn into war.

What began as a European conflict became a world war. Japan sided with the allies and seized German colonial territories in the Far East. Britain and France called on their colonies to send troops to the Western Front. Men from as far away as New Zealand and Australia, Canada, Senegal, and India were in the trenches of France. Rival forces battled one another in southern Africa and in the Middle East as well.

The United States tried to remain neutral. However, the United States would eventually be drawn into the war.

Assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, in Austrian-ruled Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina on June 28, 1914. The Archduke was heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Courtesy of Europeana, 1914–1918

Mobilization

For decades, Europe’s Great Powers of Great Britain, France, Germany, Russia, and Austria-Hungary, competed for supremacy on the continent. Mobilization of military forces caused rival nations to fear for their country’s safety. A naval and military arms race combined with an intricate system of alliances caused a chain reaction, drawing the countries of Europe to war following the assassination of Austrian Archduke Ferdinand.

Armies on all sides mobilized for what many believed would be a short war. On August 2, 1914; Europe was plunged into total war as Germany invaded Luxembourg and Belgium.

German infantry advance along the Eastern Front in Russia in 1914.

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

A German cavalry regiment occupies a Russian castle in Russian governed Poland. At the start of the conflict, modern-day Poland was divided amongst the German, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian Empires.

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

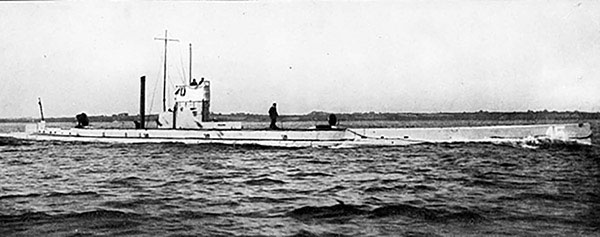

Unrestricted Submarine Warfare

Germany employs the use of submarines against merchant vessels in the hope of preventing needed war materiel from reaching the Allies, and thereby breaking the stalemate on the Western Front.

Collier's New Photographic History of the World's War, 1918

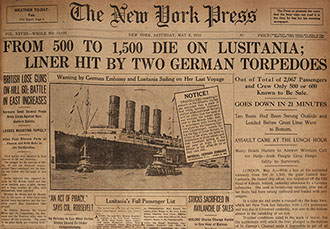

Sinking of the Lusitania

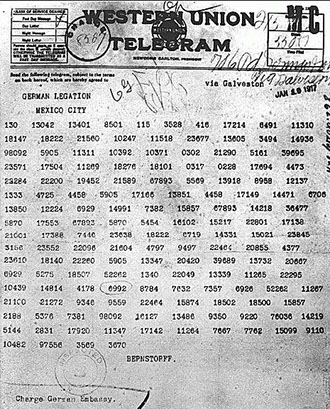

Zimmermann Note

In May 1915, the British passenger ship Lusitania is torpedoed in the Atlantic, killing 1,198 people, including 128 Americans. The outrage in America forces the Germans to end the indiscriminate sinking of merchant vessels.

Courtesy of the New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

The German foreign secretary sent a secret telegram to the Mexican Government guaranteeing German aid if Mexico would agree to go to war with the Americans. The message was intercepted and deciphered by British code breakers and subsequently leaked to the American government on February 24, 1917.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In March 1917, unrest in Russia culminated in revolution. On March 15, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated the throne in favor of a provisional government. His abdication was followed by months of unrest before the Bolsheviks under Vladimir Lenin seized power in October, sparking a civil war between “Red” communist forces and their “White” opposition. On March 3, 1918, Russia and Germany sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, formally ending the war on the Eastern Front and freeing thousands of German troops to be moved to the West.

In 1915, the Imperial Russian Government contracted with Remington Arms for one million Moisin Nagant rifles and ammunition. This rifle bears the royal crest of Tsar Nicholas II.

When revolution swept across Russia in 1917, Remington faced financial catastrophe with nobody to take the contracted rifles until the American government purchased 600,000 of the rifles to ship to the White Russian Army to combat the Bolsheviks.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1975.163.1

Bolshevik Revolution

ARTIFACTS

Austrian Roth-Steyr M1907 Pistol

This was the principal sidearm of the Austro-Hungarian armed forces during the First World War.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1978.137.6 A-C

French Gas Mask

The mask varies greatly from the English—and later American—versions and lacks a charcoal filter canister. This mask was issued to American Field Service Ambulance Driver Charles McArdell, who drove ambulances for the French Army.

Courtesy of the Joseph Alteri Collection

Belgian Army Adrian Helmet

Private Collection

German Army Gas Mask, ca. 1917

This gas mask was issued to soldiers in the Imperial German Army. The mask is constructed of a rubber-coated fabric. Some variations were also made of leather. The filter canister attaches at the mouth of the mask.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1987.73.7 A-B

German Army Machine Gunner’s Breast Plate

German machine gunners often used steel plating in addition to the steel helmet to guard against enemy fire.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1977.200.4

German Army Stahlhelm (Steel Helmet)

The Imperial German Army replaced the iconic Pickelhaube beginning in 1916 with steel helmets. The Stahlhelm design became distinctive of German military forces through both World Wars.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1977.200.3

German Army Pickelhaube (Spiked Helmet)

The Pickelhaube helmet was an iconic element of German Army uniforms. It was not designed well for trench warfare as the helmet’s leather offered no protection from shrapnel and the prominent spike made the wearer a target for opposing sharpshooters and snipers. Eventually, the Pickelhaube was replaced with the Model 1915 steel helmet.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1987.73.6

German M1908 Spandau Machine Gun, Sled Mounted

The Machinengewehr or machine gun quickly became one of the most effective weapons of the war. This German sled-mounted MG08 heavy machine gun was designed to be maneuvered by four infantry soldiers. As such, it was cumbersome for use in an attack, but deadly in an entrenched defensive role.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1977.200.1

ENLISTMENT

While the United States Government remained neutral when World War I broke out in August 1914, thousands of American citizens chose to serve with foreign armies Approximately 200 Americans served in the French Foreign Legion. Tens of thousands enlisted in the Commonwealth Forces of the British Empire—mostly in Canada—and 265 volunteered as pilots in the Lafayette Escadrille. An unknown number likely volunteered for service in the armies of the Central Powers as well.

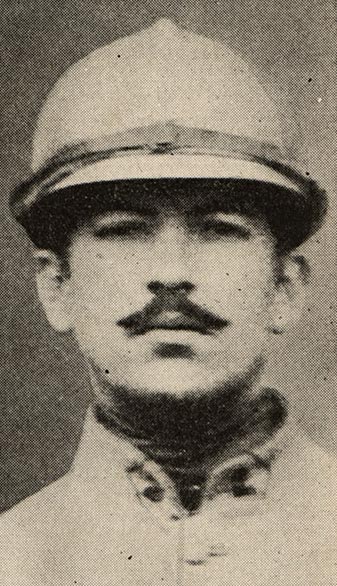

Italian American Donato Di Russo returned to his native land to serve in the Italian Army. He was killed in action on June 30, 1916.

New York State Archives

Donato Di Russo

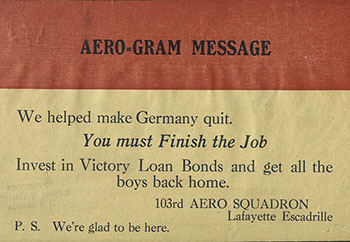

The Lafayette Escadrille was a squadron composed mostly of American pilots who fought for the French Army. The squadron was originally formed in April 1916 as the Escadrille Americaine, but soon changed its name to the Lafayette Escadrille following complaints from the German Government. It was transferred to the U.S. Army as the 103rd Aero Squadron upon American entry into the war.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Artist: Unknown

Printer: Unknown

Publisher: 103rd Aero Squadron, Lafayette Escadrille

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

Lafayette Escadrille

Aero Gram Message

Alan Seeger

June 22, 1888–July 4, 1916

An American poet born in New York City, Seeger was living in Paris when war broke out in 1914. He was educated at Harvard University and settled in Greenwich Village in 1910 before moving to the Latin Quarter in Paris. On August 24, 1914, Seeger enlisted in the French Foreign Legion; as an American citizen, Seeger was prohibited from joining the French Army directly. He was killed during the Battle of the Somme on July 4, 1916.

“Rendezvous”

I have a rendezvous with Death

At some disputed barricade,

I have a rendezvous with Death

At some disputed barricade,

When Spring comes back with rustling shade

And apple-blossoms fill the air -

I have a rendezvous with Death

When Spring brings back blue days and fair.

Excerpt from Rendezvous by Alan Seeger, 1917.

From The Literary Digest History of the World War by Francine Whiting Halsey, page 243. Published after his death, it was perhaps his most famous poem.

Alan Seeger in his Foreign Legion uniform

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

“Britishers, You’re Needed.” (1917)

Artist: Lloyd Meyers

Printer: Allen Frank & Co., New York, NY

Publisher: British and Canadian Recruiting Mission

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

Fighting for Foreign Lands

Thousands of foreign-born New Yorkers returned to Europe to defend their homelands. Three thousand Italians from Rochester returned to Italy. Statewide, the number was likely 10,000. Additionally, some 4,000 Polish residents of New York joined the Polish Legion.

Recruitment

Much of the recruitment of Americans was intentional, particularly by the British. In September 1914, Winston Churchill, First Lord of the British Admiralty, declared, “Nothing will bring American sympathy along with us so much as American bloodshed in the field.”

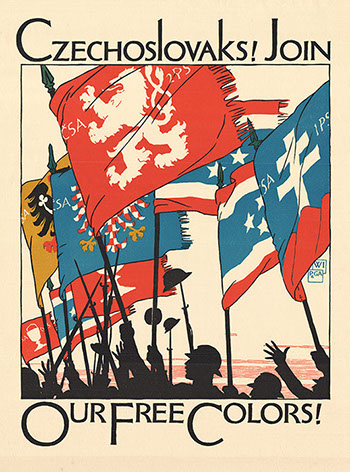

Recruitment poster for the Free Czechoslovakian Army

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

PREPAREDNESS

MOVEMENT

Following the sinking of the Lusitania and other German provocations, former President Theodore Roosevelt, Army General Leonard Wood, and others criticized President Wilson’s policy of neutrality. Roosevelt became a supporter of the preparedness movement, which sought to ready the nation’s citizens for a war that seemed unavoidable. In August 1915, the first civilian military training camp was held in Plattsburgh, New York. When the camp opened, 1,300 men—many from New York’s young business and professional class—signed up. The following summer, 16,000 attended the camp at Plattsburgh and similar camps nationwide.

Preparedness even found its way into the national pastime. Here, members of the New York Yankees practice military drills prior to a baseball game at the New York Polo Grounds in early 1917.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

New Yorkers Divided

While Roosevelt and Wood advocated for Preparedness and often urged American entry into the European War on the Allied side, several highly visible segments of the population opposed the war or favored the Central Powers. Outside of citizens of German and Austrian descent, who supported their mother countries at the outset of the conflict, many Irish Americans opposed U.S. support for Britain, who continued to occupy their homeland. Many East European Jews advocated against siding with the anti-Semitic government of Tsar Nicholas II in Russia.

Because of its large population of immigrants, New York became visible in the struggle and debate over America’s potential entry into the war. The divisions within New York society and across the nation needed to be overcome if the nation hoped to rally its citizens behind the war effort.

Military Drills

Anti-War Rally at Union Square, 1914

Attendees of this anti-war rally at Union Square in Manhattan called for the United States Government to remain neutral in the conflict on the European Continent.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

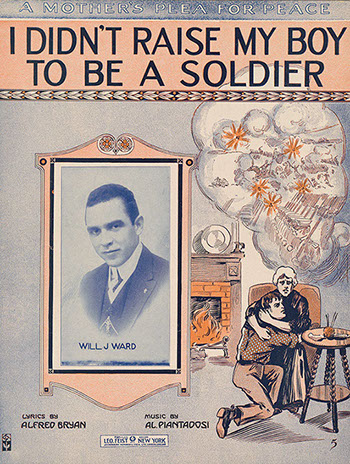

This song, first published by Leo Feist of New York City in 1915, became a hit across the United States. The anti-war sentiment was popular amongst pacifists and isolationists who opposed American involvement in the European war.

From the New York Public Library

Songsheet, “I Didn’t Raise My

Boy to be a Soldier”

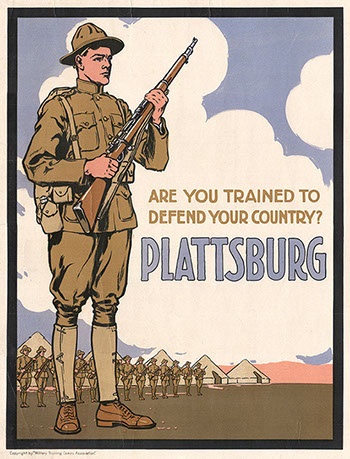

Recruitment poster for the Plattsburgh Citizens Military Training Camps that were held in the summers of 1915 through 1917.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1977.139.1

“Are you trained to defend your country?” (1915)

NAVIGATE TO NEXT SECTION

|

|

|

| Office of Cultural Education New York State Education Department Information: 518-474-5877 Contact Us | Image Requests | Terms of Use |

||