LEGACY OF WWI

The Great War dramatically transformed America’s place in the world. The horrors of war led to a reversion to American Isolationism and an abandonment of President Wilson’s new world order. Fear of communism and foreign influence continued to fuel the 100 Percent American Movement and led to increasingly restrictive immigration policies.

The Treaty of Versailles attempted to punish Germany for the war. The harsh conditions of the treaty contributed to the rise of Adolph Hitler and the Nazis and, ultimately, to a second and more costly World War only 20 years later. The Bolshevik takeover in Russia and the Western response led to decades of tension and a Cold War that lasted half a century.

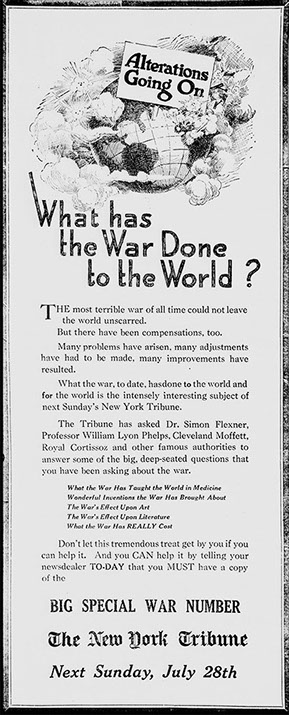

"What has the War Done to the World?"

The New York Tribune, July 25, 1918

LEGACY OF WWI: FEATURED SECTIONS

New York City skyline from Brooklyn Harbor, ships docked in foreground

Artist: Joseph Pennell, ca. 1921

Medium: Watercolor

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In October 1917, Bolshevik forces in Russia succeeded in overthrowing the Provisional Government that replaced Tsar Nicholas II. The communist takeover in Russia caused Britain, France, and the other allied democracies—including the United States—to fear communist revolutions in their own nations.

In 1919, as the American economy retracted with the loss of wartime contracts, the fragile peace between industry and labor came to an end and labor strikes erupted across the nation. Opponents of organized labor, often aided by government officials, blamed this labor unrest on communist agitators. The overriding fear of communist radicals was used by the government to continue the suppression of dissent that had been established during the war. Raids, arrests, and deportations of suspected radicals took place across the country. In New York, the mistrust of foreigners that had emerged during the war once again manifested in the postwar years. Jews and other Eastern European immigrants were suspected of being Bolshevik agents.

REPERCUSSIONS: A WORLD TRANSFORMED

For all the horror, repression, and bleakness that came out of the war, there was a positive side for many New Yorkers—a sense of unity and duty—a “spirit of sacrifice” in a public cause, and a feeling of pride and patriotism.

Politicians including Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Herbert Hoover, and others, who served in various roles during the war, gained valuable policy experience in Washington and New York City.

New York retained its status as the world’s leading port. The city’s financial sector had made the United States the leading creditor nation in the world, and, by 1925, New York was the world’s most populous city.

NEW YORK AND THE GREAT WAR

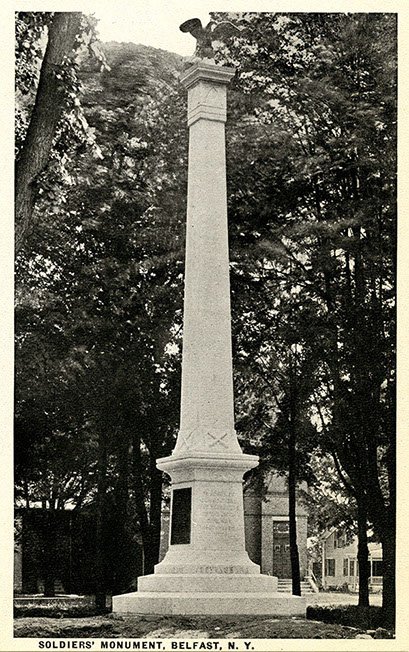

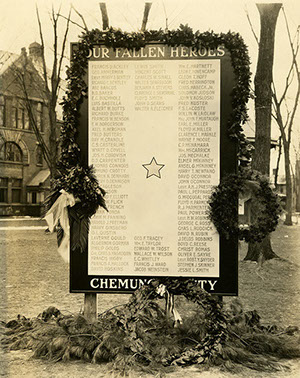

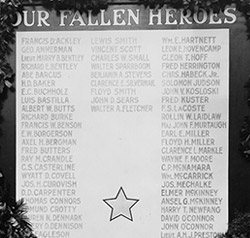

Monuments to Great Men and Women

Communities across New York State erected monuments and memorials to honor the local men and women killed during the First World War.

CHEMUNG COUNTY MEMORIAL

BELFAST, NEW YORK

HERO PARK, STATEN ISLAND

THE RED SCARE

Anti-Communism

This image graphically depicts the widespread fear in Germany—and elsewhere—of the danger posed by the communists and other radical organizations.

"Tretet der Antibolschewistischen Liga” (Join the Anti-Bolshevist League)

Artist: Krotowski

Printer: Unknown

Publisher: Propaganda Verlag

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

Terrorism on Wall Street

This photograph shows the aftermath of the September 16, 1920, bombing on Wall Street in New York City. Through acts of terrorism such as this, a relatively small group of radical extremists hurt the American Left and labor movements.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Beginning in May 1917, the United States Congress passed legislation to limit immigration. The legislation initially applied to enemy aliens from Germany and Austria-Hungary, but policies were expanded to include those suspected of being adherents to socialist, communist, or anarchist political groups. These laws disproportionately targeted immigrants from Russia and Eastern Europe. Jewish immigrants were also often turned away for suspected radical affiliations.

In 1921, federal legislation established strict quotas on the number of immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe permitted to enter the United States each year. The laws targeted Jews, Catholics, and other groups deemed racially inferior to Americans of North European heritage. A revised Immigration Act in 1924 limited immigration to two percent of the foreign-born residents of each nationality already residing in the United States. These laws remained in effect through the 1930s and ultimately prevented the escape of an unknown number of Jews from Germany and Europe following the rise of the Nazi Party.

The government also enacted a program of deportation as a weapon against foreign-born radicals. It was not until 1965 that New York Congressman Emanuel Celler introduced legislation that began to reverse the trends of restrictive immigration.

END OF MASS IMMIGRATION

Ellis Island

During World War I, the former U.S. Immigration Station at Ellis Island was converted for use as a detention center for enemy aliens and suspected spies and saboteurs. The island’s use as a detention facility continued after the war during the “Red Scare” for the detention of suspected socialists and other radicals.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Emma Goldman’s Deportation Photograph, 1919

Goldman, a suspected radical in New York, was imprisoned for conspiring against the draft. She was ultimately deported to the Soviet Union.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The First World War gave rise to an intense debate over civil liberties and rights. The passage of the federal Espionage Act in 1917 and the Sedition Act in 1918 resulted in much debate in New York State over the role of the government and the right of freedom of speech. The Espionage Act empowered the government to regulate any speech deemed helpful to the enemies of the United States, while the Sedition Act made it a crime to make disloyal statements against the U.S. government or its allies. The United States Supreme Court upheld convictions of several New Yorkers for the act of distributing revolutionary material.

The federal government also initiated a policy of forcible deportation of alien residents who adopted radical philosophies. Many of these “unwanted aliens” were detained at Ellis Island in New York Harbor before being returned to their homelands. All of these debates over civil liberties prompted the formation of the American Civil Liberties Union in New York City in 1920.

CIVIL RIGHTS

Lynchings

A flag flies outside the N.A.A.C.P. headquarters on Fifth Avenue in New York City announcing a lynching, 1936. The summer of 1919 witnessed the lynching deaths of more than 100 African American veterans and race riots in Chicago, Washington, and elsewhere as the prewar social order attempted to reassert itself in the face of challenges by African Americans.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

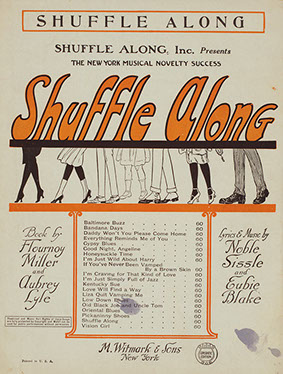

The return of the 369th Infantry Regiment Harlem Hellfighters on February 17, 1919, marked a celebration. A sense of pride in the veterans themselves, as well as in New York’s African American population, that their service to the nation provided indisputable evidence of their commitment as American citizens that should have placed them on equal footing with white veterans. Their homecoming coincided with the emergence of a cultural awakening of African American art, music, and literature known as the Harlem Renaissance. Several veterans of the 369th emerged as leading figures in the Harlem Renaissance, including Noble Sissle, whose partnership with jazz composer and pianist Eubie Blake produced Shuffle Along, the first Broadway musical by African Americans and featuring blacks on stage in 1921.

Across the nation, asserting that the World War was a turning point in race relations, leaders of the N.A.A.C.P. and others called forth a “New Negro”—a philosophy born of the experiences of black troops in World War I and their determination to “achieve fuller participation in American Society.” Civil rights leaders pushed for the passage of anti-lynching legislation in Congress and sought to ensure equal access to benefits for black veterans.

HARLEM'S RENAISSANCE

Shuffle Along, by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake (1921)

The first Broadway musical produced African Americans and that featured blacks on stage.

Courtesy of the New York State Library

Grave Marker

This 1950s-era grave marker honored a soldier of Battery C, 104th Field Artillery, 27th Division. The New York National Guard Artillery Regiment served with the New York Division from the Mexican Border in 1916 through the end of World War I.

New York State Military Museum, Division of Military and Naval Affairs

The legacy of World War I is substantial. In terms of the human cost, 48,909 Americans were killed in battle, an additional 63,523 died from disease, and more than 230,000 were wounded. Of those killed, 14,000 were from New York State. Globally, more than 17 million people were killed, including over 7 million civilians, and 20 million others were wounded.

Perhaps the most significant legacy of the Great War, however, was how much the conflict left unresolved. World War I was not the “War to End All Wars,” and in fact laid the conditions for a larger and more deadly war. America did not emerge as a world leader after the war, but rather withdrew to the apparent safety of its two oceans. The care of the millions of young men and women who answered the call to arms was left largely unanswered until after World War II.

LASTING LEGACY

NAVIGATE TO NEXT SECTION

|

|

Office of Cultural Education New York State Education Department Information: 518-474-5877 Contact Us | Image Requests | Terms of Use |