Whoever said a picture is worth a thousand (or ten thousand) words never was more correct than when describing the value of visuals in creating images of life in the past. Because of movie and television screens, we have become a visual society and make decisions more on what we see in the media than on what we have read. In other words, we are different from our forebears and fundamentally different from the people of colonial Albany whose world view was confined to what they could see with their own eyes or what if anything they could read.

Today, most people are literate and everyone has access to a volume and array of printed information that would astound even the most forward thinking eighteenth-century person. However, most people make judgments quickly and few of us have the patience to read through and absorb even the shortest passages. While the written word remains a favorite of the modern historian's programming tool chest, effective presentations today involve pictures, portraits, and maps, and the most effective and inspiring programming is visually based.

Gaining a visual perspective on the people of colonial Albany and their world has been an enlightening and frustrating experience for the community historians at the Colonial Albany Social History Project. Basic to our overall program is the need to visualize the pre-industrial community and to appreciate the look and feel of everyday life. Over the past decade, project research has addressed these issues. At this point, we have identified and captured on film most of the known visual representations of early Albany and its people. Many of these historical treasures are more than 200 years old and are held in historical museums such as the Albany Institute of History and Art, the New York State Museum, and Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site. Other materials are less centrally held in public repositories (including the New York State Library and State Archives), in private collections, and on a more individual basis. At the same time, we believe that much more material has survived and remains to be re-discovered.

Our search of the traditional historical record and of the most important cultural repositories has yielded material that has become a "Graphics Archive" of several thousand images. These include portraits, paintings, drawings, maps, documents, slides of three-dimensional objects in museum and private collections, and a growing collection of "historical art." This last group of 19th and 20th century materials includes two and three-dimensional materials - paintings and drawings, modern photographs, images of reproduction artifacts and revival architecture, and a video library of useful tapes.

James Eights was Albany's first great historical artist. He painted the community he remembered while growing up in Albany during the early nineteenth-century. Interpreted often, reproduced liberally, and presented in most of the traditional histories of the city, his mid-nineteenth century recreations of early Albany scenes have inspired all students of early Albany.

Until recently, virtually all of the creditable historical artwork focused on early Albany has been derivative of the work of James Eights. At first glance, one might be tempted to discount the early twentieth-century depictions of newcomer David C. Lithgow. Beholding to Eights, but even more victorianized, nevertheless the Lithgow paintings and murals do come with some recommendation. Most persuasive for us is that they sometimes offer the only visual perspective on an important event in Albany's past. And also, who doesn't like brightly colored.

During the 1980s, a new artist appeared on the historical horizon unveiling a set of paintings and drawings that were very different from the Eights streetscapes and building portraits.

Trained as an architect, Leonard F. Tantillo sought to interpret important historical themes by visualizing new and important elements of the early Albany story. The fact that each of his paintings also was based on substantial historical research gave Tantillo's historical art a dimension not much utilized in the past.

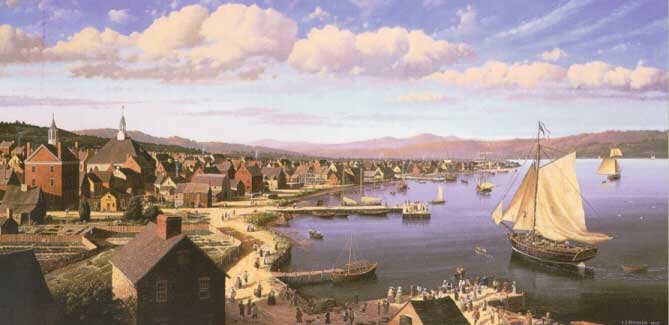

After completing a panoramic view of the Albany Basin as it might have appeared just after the Civil War and a startling painting of Fort Orange in 1635, he first collaborated with the Colonial Albany Project in 1985 on a project to produce an exhibit and book commemorating the 300th anniversary of Albany's city charter. Based on maps, property records, consultation with us and many others, and much personal research, Len produced a set of four pen-and-ink drawings of Albany in 1686. Three scenes commemorating the first meeting of the Albany Common Council, the fur trade, city life on Court Street, and a detailed birds-eye diagram of how the city looked at the time of its chartering have become the most useful and popular representations of early Albany life.

Working in concert with Colonial Albany Project staff and with a larger network of historians and other advisors, Tantillo has created more than a dozen historical pieces that have breathed life into historical programs and presentations in Albany and beyond. Also, prints of these handsome paintings are widely found in homes, offices, and public buildings - inspiring images of city life in the past. These works have run the chronological gamut from a representation of the trading house on Castle Island in 1615 to the Hudson River Day Line Ticket Office in the early 1900s. In 1996, the Art Gallery and Museum at the State University at Albany opened an exhibition of Tantillo's work entitled Visions of New York State: The Historical Paintings of L.F. Tantillo. Because the artist paints more to convey a sense of the past rather than for "art for art's sake," this exhibition has been controversial and has inspired some discussion in regional arts circles over its merits and value. At the same time, Visions of New York State was the most popular exhibition in the history of the University Art Gallery.

With an unparalleled ability to make diverse people appreciate and understand that "history happened here", we believe that Len Tantillo is the most effective interpreter of the city's past. His work has a profound effect on the overall progress of the Colonial Albany Social History Project. His creations and the questions he and others have raised regarding them have led us to consider the community's past in much more than grammatical terms. As he continues to create new images that move in on the community and the lives of its people, we have been blessed with a powerful programming tool.

first posted: 1999; last revised 4/24/15