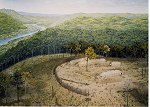

A MOHAWK IROQUOIS VILLAGE - Section 3

8. Four hundred years ago, Iroquois villages were usually located on the tops of steep-sided hills. The steep slopes formed natural defenses for the village; a palisade or "stockade" was commonly built along the edge of the hill for added protection. Notice the entrance to the village through a narrow space formed by overlapping ends of the stockade wall. This "tunnel" could be defended from intruders. Some villages had two or three rows of palisades around them.

8. Four hundred years ago, Iroquois villages were usually located on the tops of steep-sided hills. The steep slopes formed natural defenses for the village; a palisade or "stockade" was commonly built along the edge of the hill for added protection. Notice the entrance to the village through a narrow space formed by overlapping ends of the stockade wall. This "tunnel" could be defended from intruders. Some villages had two or three rows of palisades around them.

The Iroquois used a style of farming, known today as "slash-and-burn" or "swidden," that requires a community to move the location of its village from time to time. As the soils of the fields became exhausted, and firewood in the neighborhood became scarce, the people had to venture farther afield for these essentials of life. After awhile, the distances traveled for both became too inconvenient and difficult. For these reasons, and because the longhouses and palisades needed more and more repair, the community would decide to create a new village a few miles away.

Detail from The Village Model, A Mohawk Iroquois Village, c.1600. New York State Museum, Albany, NY.

9. The Iroquois cut a clearing in the forest to create a space for the village and the surrounding fields. The village was located on the hilltop for defense and good drainage. Soil fertility determined the location of the surrounding fields. A water supply, either a spring or stream, was located nearby.

9. The Iroquois cut a clearing in the forest to create a space for the village and the surrounding fields. The village was located on the hilltop for defense and good drainage. Soil fertility determined the location of the surrounding fields. A water supply, either a spring or stream, was located nearby.

The larger the population of a village, the more quickly did the nearby resources such as firewood and fertile fields become exhausted. A small village might be able to maintain itself in one location for 20 to 30 years, but a large village might need to move in ten years. The move itself and the decision to move were not made quickly. They were the result of months, if not years of planning.

Perhaps a year or two before the move, the villagers identified a new location in the surrounding forest. The forest would be cleared to create the site for the village and for the fields. Rather than everyone from the "old" village moving to the "new" village at the same time, the move probably took place over a period of months, perhaps a year. Families from the old village moved to the new village as longhouses were completed and as fields came under cultivation. A few people may have chosen to stay at the old village, at least for a while.

Detail from The Village Model, A Mohawk Iroquois Village, c.1600. New York State Museum, Albany, NY.

10. New villages probably were built over a period of time, with longhouses being occupied as they were built, then new construction started along side them. All this time people were coming and going to and from the old village. Residents of the new longhouses might be busy at work making clay pots or pounding dried corn into flour using a large wooden mortar and pestle.

10. New villages probably were built over a period of time, with longhouses being occupied as they were built, then new construction started along side them. All this time people were coming and going to and from the old village. Residents of the new longhouses might be busy at work making clay pots or pounding dried corn into flour using a large wooden mortar and pestle.

The forest that was cleared to create the new village site and farm fields around it provided the raw materials for the construction of the new village. Small trees and saplings provided the wooden posts, poles, and bark lashings for the frameworks, and larger trees supplied the bark sheets for covering the longhouses. Some parts for the longhouses and palisade may have been salvaged from the old village and carried to the new site. The building materials were collected, prepared, and gathered at the new site weeks and months before construction began. The collection and preparation of the raw materials took a great deal of time and effort. Putting up the longhouse was relatively easy and quick, and accomplished by a "longhouse-raising-bee," drawing upon the help of all who would live in it, and perhaps their neighbors.

Detail from The Village Model, A Mohawk Iroquois Village, c.1600. New York State Museum, Albany, NY.

11. The symbol of the extended family's clan was frequently painted on the outside end of the longhouse to identify its residents. Among the Mohawks, this would either be a turtle, wolf, or bear. The one shown here, painted in red, is a stylized "Bear". It indicated that this was a longhouse of the Bear Clan, whose female residents were "sisters" who worked and lived together. Adjacent longhouses might be the homes of extended families belonging to the same clan, or they might be home to families of another clan.

11. The symbol of the extended family's clan was frequently painted on the outside end of the longhouse to identify its residents. Among the Mohawks, this would either be a turtle, wolf, or bear. The one shown here, painted in red, is a stylized "Bear". It indicated that this was a longhouse of the Bear Clan, whose female residents were "sisters" who worked and lived together. Adjacent longhouses might be the homes of extended families belonging to the same clan, or they might be home to families of another clan.

The girls learned various skills and crafts, such as pottery-making, from their "mothers," "aunts," and "grandmothers." Today, on the basis of distinctions in techniques and decorations, archeologists can often distinguish the pottery made in one longhouse from that made in another longhouse nearby. Relying on these same distinctions, archeologists can also trace the movements of families and communities from one village location to another.

But it was not all work and no play. Amusements and recreation were also important parts of Iroquois village life 400 years ago. Stories, riddles, and jokes would be told, even as you worked, especially, in the cold of winter, when the weather confined everyone in their longhouses. Games of chance, for instance, those using circular dice made from deer antler, would be played. Children role-played and or just had a "good time."

Detail from The Village Model, A Mohawk Iroquois Village, c.1600. New York State Museum, Albany, NY.

12. When weather permitted, a lot of work was done outside where the light was better and the air relatively free of wood smoke. Food was continually being prepared and cooked. There were no set mealtimes. Family members helped themselves from the pot whenever they were hungry.

12. When weather permitted, a lot of work was done outside where the light was better and the air relatively free of wood smoke. Food was continually being prepared and cooked. There were no set mealtimes. Family members helped themselves from the pot whenever they were hungry.

Foods raised by the Iroquois women included corn, beans, and squash; other plant foods were gathered from the surrounding forest, and included in season, roots and tubers, greens, berries and other fruits, and nuts. Fish, waterfowl, and deer and other mammals were caught, trapped, and hunted throughout the year and were the major sources of protein. Animal skins provided clothing and robes. Hunting activities were "men's work" in which younger brothers and older sons assisted. Dogs were not so much family "pets," as watchdogs and the companions of hunters. Originally, they were the only domesticated animals kept by the Iroquois and their ancestors.

Detail from The Village Model, A Mohawk Iroquois Village, c.1600. New York State Museum, Albany, NY.

13. Boys played the "hoop and javelin" game, in which boys took turns trying to throw their javelin or spear through a small hoop rolled along the ground by another.

13. Boys played the "hoop and javelin" game, in which boys took turns trying to throw their javelin or spear through a small hoop rolled along the ground by another.

Most children's toys and games involved role-playing: that is, girls doing things that their "mothers" and older "sisters" would do; boys doing what their " fathers," "uncles" and older "brothers" would do. Boys role-played as hunters and warriors using small bows and arrows, testing their skills by shooting at targets or small animals and birds. Lacrosse, known to the Iroquois as "The Little Brother of War," also drew upon and tested skills that would become important to boys in adulthood.

Girls played with cornhusk dolls, which prepared them for their important roles of life-givers and "nurturers." Field hockey or shinney may have evolved from games played by girls in the cornfields using their wooden hoes as "hockey" sticks, and any available rounded object, such as a stone or nut, as the ball.

Detail from The Village Model, A Mohawk Iroquois Village, c.1600. New York State Museum, Albany, NY.

14. The new field, cleared by slash-and-burn from a patch of the forest, was littered by charred tree stumps and large, partially burnt tree trunks. Iroquois women worked around them in the spring, planting corn, beans, and squash seeds. These were frequently planted together, spacing them amid the charred forest litter.

14. The new field, cleared by slash-and-burn from a patch of the forest, was littered by charred tree stumps and large, partially burnt tree trunks. Iroquois women worked around them in the spring, planting corn, beans, and squash seeds. These were frequently planted together, spacing them amid the charred forest litter.

Once the corn plants grew "knee-high" in June, they had to be "hilled" by hoeing soil up around their bases, otherwise, the wind or a hard rain would knock the plants over because of their shallow roots. Eventually, tall cornstalks served to support climbing beans. The large and broad leaves of squash and pumpkin plants spread out below and shaded the soil, helping to hold moisture in and preventing weeds from growing.

Freshly cleared fields were very fertile. The sites for the fields were chosen because of the high lime content of their soils, indicated by the kinds of plants, shrubs, and trees growing on them. Although some soil nutrients were lost when the clearing was burnt over in spring to rid it of weeds, brush, and unwanted fallen tree trunks and stumps, the same fires produced wood ash, rich in potassium, which helped to fertilize the soil. Although most trees were cleared, some very large trees, stripped of their bark, dead, and partially burnt, remained. Aware of the dangers of falling limbs, workers in the field avoided these whenever possible, especially during high winds.

Detail from The Village Model, A Mohawk Iroquois Village, c.1600. New York State Museum, Albany, NY.