"OVER THERE"

"OVER THERE": FEATURED SECTIONS

Under Commander General John J. Pershing, the American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.) deployed troops to Europe. The first American troops landed in Europe in June 1917—but few American troops arrived before 1918. By then, the armies of France and Britain were exhausted and desperate for reinforcements. Both the British and French wanted American troops to become part of their armies rather than wait for the American Army to be brought entirely up to strength. American Expeditionary Force Commander General John Pershing, however, insisted the U.S. Army remain independent.

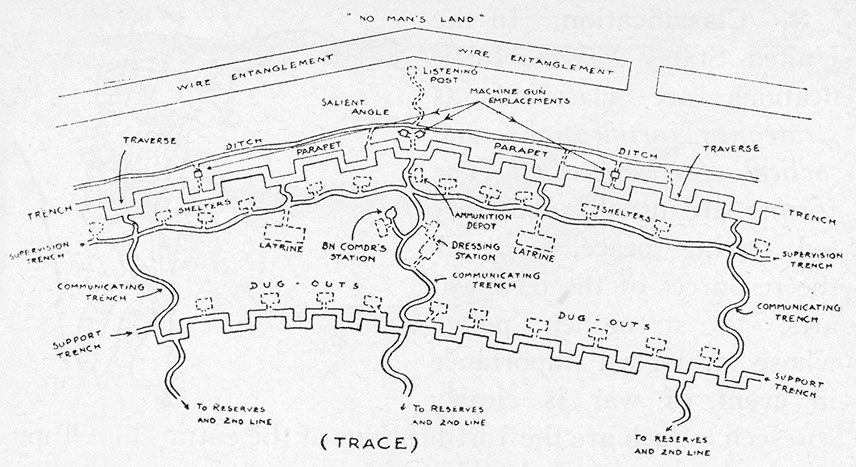

Trenches ran “twisting and turning” across the countryside—along hillsides and even through villages and towns. They were exposed to the cold and rain and mud, as well as enemy fire. Soldiers in the trenches endured an endless cycle of nighttime maneuvers and raids. Snipers and artillery fire during the day often separated long periods of boredom. At dawn and dusk, soldiers were ordered to "stand to" in case of an enemy assault. Chores, inspections, writing letters, or playing cards filled the day. Soldiers slept when they could. The tedium of this routine was abandoned when the order came to go “over the top.”

Disease, vermin, mud, and the stench of thousands of men living and dying in close quarters tormented soldiers in the trenches. Dysentery, typhus, cholera, gangrene, and “trench fever” were as great a threat as combat.

LIFE IN THE TRENCHES

Poison Gas and Trench Warfare

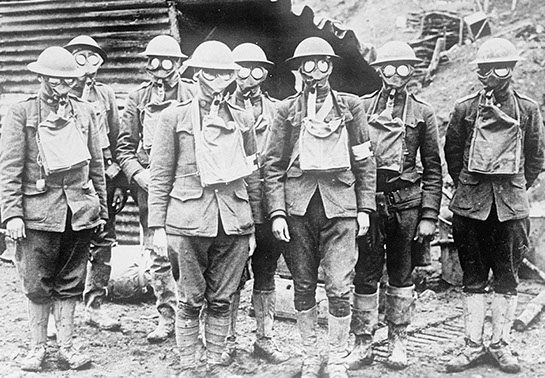

American Soldiers in Gas Masks, 1918

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Poison gas was first introduced to the battlefield in 1915 by the German Army at the Second Battle of Ypres. Gas could kill quickly or cause permanent damage. The Germans had first used chlorine gas. Soon, armies were making use of phosgene and mustard gas. Mustard gas caused severe burn-like blisters when inhaled or in contact with the skin. Since gas was denser than air, those most affected were nearer the ground, in the trenches or wounded and unable to move.

Inexplicably, not all American troops received proper training to deal with gas attacks. New Yorkers experienced the horror of this new warfare on March 20–21, 1918, when the Germans fired approximately 400 mustard gas shells into the American lines. Tragically, the men of the 42nd Division had received little training in how to deal with gas attacks and suffered 417 casualties.

Diagram of a Trench System

Misery, Cold and Fatigue

“It is a miserable life to be condemned to, shivering in these wretched holes, in the cold and the dirt and semidarkness … The increasing cold will make this kind of existence almost insupportable, with its accompanying vermin and dysentery … The real courage of the soldier is not in facing the balls, but the fatigue and discomfort and misery.”

— Alan Seeger, November 14, 1914

Mealtime in the American Trenches

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

The order to go “over the top” directed soldiers to climb out of the trenches and cross "No Man’s Land" (the area between opposing trenches) to attack enemy lines. Usually artillery barrage (massed firing from large-caliber guns) started the command, followed by soldiers charging across No Man’s Land. Leaving the protection of the trenches was extremely dangerous. Artillery fire, land mines, and barbed wire made it difficult to gain ground.

Over the Top

Photo taken by a German, showing American soldiers going over the top

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

Soldiers of the 107th are seen training alongside British tanks in preparation for the assault on the Hindenburg Line.

Courtesy of the New York State Military Museum, Division of Military and Naval Affairs

ARTIFACTS

U.S. ARMY GAS MASK & RESPIRATOR

GAS ALARM

EYE GLASSES

WRISTWATCH

WHISTLE

WIRE CUTTER

TRENCH KNIFE

U.S. LEWIS AIRCRAFT MACHINE GUN

ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCE

The organization of the army consisted of divisions of 30,000 men, including infantry, artillery, and supply units. This was about twice the strength of British or French divisions. Divisions 1 to 20 were assembled from the Regular Army and volunteer enlistees. Divisions 26 to 42 were designated for the National Guard units from across the country, and 76 to 93—designated the National Army—were composed of draftees. In addition to the National Guard units from New York, New Yorkers could be found in nearly every Regular Army and National Army division.

27th DIVISION

The New York State National Guard Division was designated the 27th Infantry Division on July 20, 1917. When it sailed for France, the 27th numbered 991 officers and 27,114 enlisted men. New York’s 27th “Empire” Division was one of four divisions composed of soldiers from a single state.

In the spring of 1918, a new German offensive threatened Paris. Commander General John Pershing allowed two divisions to be assigned to the British Army as distinctly American divisions with American officers.

After training with the British, the 27th Division entered the trenches in Belgium. For nearly two months, the New Yorkers worked to fortify their position against anticipated enemy attack. On August 31, 1918, the 27th Division assaulted Mont Kemmel, capturing the hill on September 2. After this initial combat experience, the 27th was sent to the rear in preparation for the Somme Offensive.

Major General John F. O’Ryan

27th Division

(1874-1961)

Born in Manhattan, O’Ryan was the son of an Irish immigrant. While a student at the College of the City of New York he enlisted as a private in the 7th Regiment of the New York Militia. After graduating from New York University in 1898, he embarked on a legal career in New York City. He continued to serve in the militia, rising through the ranks. In 1912 O’Ryan was promoted to Major General and given command of the New York National Guard. He was appointed to the U.S. Army War College by General Leonard Wood in 1914—a rare event for National Guardsmen of the era. In 1916, he led the New York National Guard Division when it was ordered to the Mexican Border. Before World War I, O’Ryan became a proponent of the Preparedness Movement and the Plattsburgh Training Camps. He led the New York National Guard Division throughout the war.

Following World War I, O’Ryan returned to civilian life as an attorney and held a variety of civilian and government positions. In World War II, he served as director of civil defense.

Major General John F. O'Ryan, 1917

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Battle of the Hindenburg Line

The Hindenburg Line was a system of trenches, barbed wire, and concrete fortifications situated almost halfway between the North Sea and the Swiss border. The position formed a pivot point that needed to be overcome before French and American forces to the south, and the British to the north, could begin an overall advance.

The 27th Division, along with the 30th Division, was selected to lead the attack on the Hindenburg Line. On September 27, 1918, the American divisions supported by British artillery and two Australian divisions began the assault. Over the next 24 days, they struggled to drive the German defenders from their fortifications.

Aerial view of a sector of the Hindenburg Line

New York State Museum Collection, H-1981.25.10.4

Private Peter Schaming, Jr.

27th Division

(1901-1973)

Sixteen-year-old Peter Schaming, Jr. dropped out of Curtis High School on Staten Island and enlisted in the New York National Guard on April 12, 1917, just one week after the declaration of war. Schaming was assigned to the 106th Infantry Regiment of the 27th Division.

The 106th Infantry Regiment was primarily composed of New York National Guardsmen from Brooklyn and the Southern Tier. At the start of the war, the 106th had a total effective strength of 3,003 officers and men. During its service in World War I, the 106th sustained 1,955 casualties, including 1,496 wounded, 376 killed, and 83 who later died of their wounds.

“I have been in the trenches again and I am one of the very few who is still alive and haven't a scratch on me. My regiment the 106th Infantry is wiped out. How I ever got out alive is more than I can tell.”

--Private Peter Schaming, October 1, 1918

Peter Schaming

Courtesy of the Schaming Family

77th DIVISION

Variously called the “Liberty” or “Melting Pot” Division, the 77th Division was organized at Camp Upton, Long Island, and was raised almost entirely from conscripted soldiers from the New York City region. Even as immigrants fell under suspicion at home, the 77th Division reflected New York City’s cosmopolitan character. As noted by James Sullivan, New York State Historian of the time, “Many could not speak English. There were Italians, Jews, Chinese, Irish, Armenians, Syrians and other nationalities, rubbing elbows with the native born.”

The 77th Division arrived in France in April 1918 and was the first division of drafted soldiers to arrive in France, the seventh division of the A.E.F. in Europe. The Division saw its first combat during the Battle of Chateau-Thierry on July 18.

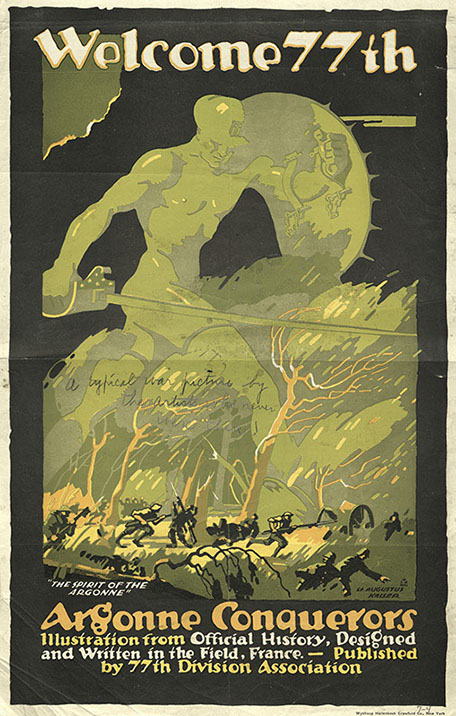

Field History of the 77th

This poster was an advertisement for the 1919 publication of the History of the 77th Division, which was produced for the division’s return to the United States. Mars, the Roman God of War, is depicted leading the fight in the Argonne.

Argonne Conquerors

Artist: Lt. Augustus Kaiser

Printer: Wynkoop, Hallenbeck, Crawford Co., New York, New York

Publisher: 77th Division Association

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

One battalion of the 308th Infantry Regiment advanced beyond either of its flanking units and found itself surrounded behind enemy lines. Under the command of Major Charles Whittlesey, the “Lost Battalion” held out under murderous German fire for six days with little food, fresh water, or ammunition. Their stalwart defense forced the German Army to expend resources to dislodge them and aided other American units to force a breakthrough.

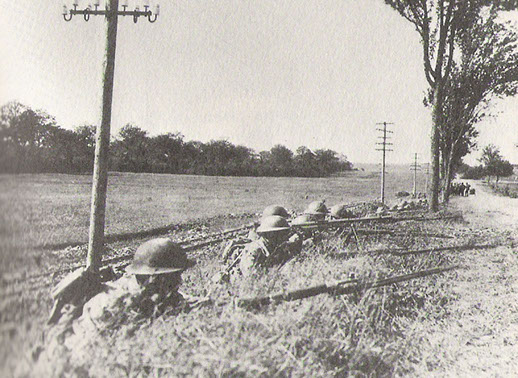

American soldiers advancing during the opening days of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

The Argonne Forest

During the Allied Meuse-Argonne Offensive (September 26-November 11, 1918), the 77th Division was tasked with clearing a three-mile-wide portion of the Argonne Forest. As the division advanced over the rugged, forested terrain, communication between units quickly broke down.

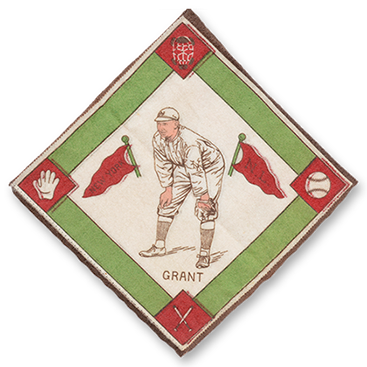

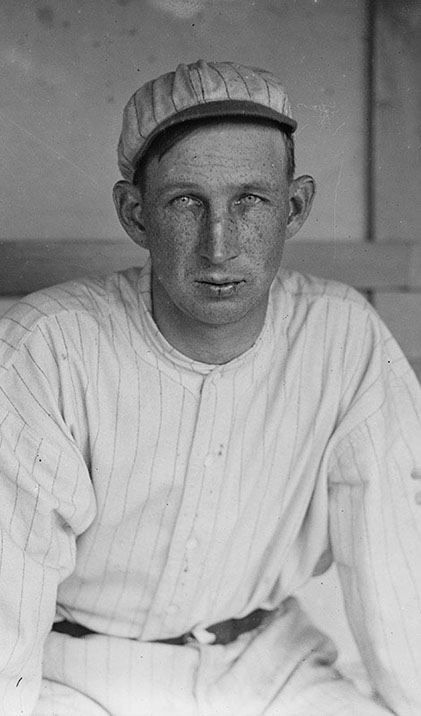

Captain Edward “Eddie” Grant

307th Infantry Regiment, 77th Division

(1883-1918)

Grant was born in Franklin, Massachusetts, and educated at Harvard University. After graduation, he pursued a career as a professional baseball player with the Cleveland Indians, Philadelphia Phillies, Cincinnati Reds, and the New York Giants from 1913 to 1915, including the 1913 World Series Championship team. Grant retired after the 1915 season and became a lawyer in Manhattan.

In the summer of 1916, he attended the Plattsburgh Citizens Military Training Camp where he befriended Charles Whittlesey. When war was declared, Eddie Grant volunteered for military service despite the fact that at age 34 he was beyond draft age. He became a company commander in the 307th Infantry Regiment, 77th Division.

Eddie Grant was killed on October 5, 1918 leading an effort to rescue Major Whittlesey and the Lost Battalion in the Argonne Forest.

In 1921, the New York Giants erected a memorial plaque in Grant’s honor at center field at the New York Polo Grounds.

Grant in his New York Giants uniform

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Quilt Square

This 1914 felt features the likeness of New York Giants infielder Eddie Grant. Tobacco felts were produced by several companies and would have been fastened to tobacco products as a collectible item. The felts were often sewn together to create quilts.

New York State Museum Collection, H-2016.11.1

165th INFANTRY REGIMENT / 42nd DIVISION

As the nation rushed to mobilize, states competed to be the first to send their National Guard units to France. In response, the War Department announced the formation of the 42nd “Rainbow” Division, which included units from 26 states and the District of Columbia. The old “Fighting 69th” was New York’s contribution to the division and became the 165th Infantry Regiment of the 42nd Division.

The 42nd Division arrived in France in November 1917. Shortly after Christmas, the men of the 165th undertook an 80-mile march through the Vosges Mountains to Longeau where the regiment was placed into the line. The 165th first saw combat on February 26, 1918 in the Chausilles sector near the village of Baccarat. The regiment fought with distinction at Chateau-Thierry, St. Mihiel, and during the final Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Its commander, Colonel William Donovan, earned the Medal of Honor on October 14–15, 1918, for his actions near Landres-et-St. Georges, France.

Soldiers of the 165th Infantry in France

Courtesy of the US Army Signal Corps via Wikimedia Commons

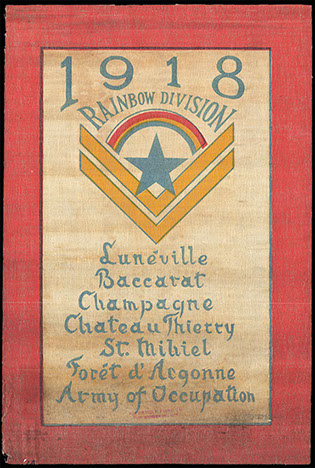

Window Banner

This window banner bears the rainbow insignia of the 42nd Division and lists the battles in which the unit—including New York’s 165th Infantry Regiment—fought during the war. When the formation of this division from units of several states was proposed, it was said such an organization would "stretch over the whole country like a rainbow” giving it the nickname “Rainbow” Division.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1988.72.2

Sergeant Richard O’Neill

Company D, 165th Infantry Regiment, 42nd Division

(August 28, 1898–April 9, 1982)

Richard O’Neill grew up in Harlem, New York. He joined the 69th Infantry Regiment of the New York National Guard and was a sergeant in the unit at the outbreak of war. O’Neill was assigned to Company D, 165th Infantry when the regiment was rushed into the line in the face of the German Army’s major offensive in July 1918. After forcing the enemy into retreat on July 15, the 42nd Division joined in the pursuit of the German Army.

On July 30, 1918, during the Aisne-Marne Offensive, O’Neill earned the Medal of Honor for “extraordinary heroism” at the Ourcq River in France. According to the Medal’s citation:

“In advance of an assaulting line, Sergeant O'Neill attacked a detachment of about 25 of the enemy. In the ensuing hand-to-hand encounter he sustained pistol wounds, but heroically continued in the advance, during which he received additional wounds; but, with great physical effort, he remained in active command of his detachment. Being again wounded, he was forced by weakness and loss of blood to be evacuated, but insisted upon being taken first to the battalion commander in order to transmit to him valuable information relative to enemy positions and the disposition of our men.”

O’Neill’s actions reportedly caused confusion amongst the German defenders and forced them into retreat. Sergeant Richard O’Neill was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1921 by President Warren G. Harding. He emerged from the First World War as one of New York State’s most decorated soldiers.

Sergeant Richard W. O’Neill, shown with the Medal of Honor around his neck

Courtesy of The Disabled American Veterans of the World War. Chicago via Wikimedia Commons

The Medal of Honor

Sergeant Richard O’Neill was awarded in 1921

Courtesy of the New York State Military Museum,

Division of Military and Naval Affairs

and the Veterans of the 69th Infantry Regiment Association, Lexington Avenue Armory, New York, New York

369TH INFANTRY REGIMENT

The 15th New York was the only American unit to arrive in France with its state designation. The regiment was re-designated the 369th Infantry Regiment and was assigned to the 93rd Division, a proposed all-black division in the segregated U.S. Army. The division was never formed; the 369th was instead assigned to the French Army, which was depleted from four years of war and eager to employ able-bodied fighters regardless of color.

Confronted by racism in the segregated United States Army, the men of the newly federalized 369th Infantry were put to work digging latrines and serving as stevedores unloading ships at harbor. The unit commander, Colonel William Hayward, eventually convinced the American command to allow his men to fight—but under French Army command.

Soldiers of the 369th Infantry Regiment in training with the French Army

New York State Museum Collection, H-2010.45.8

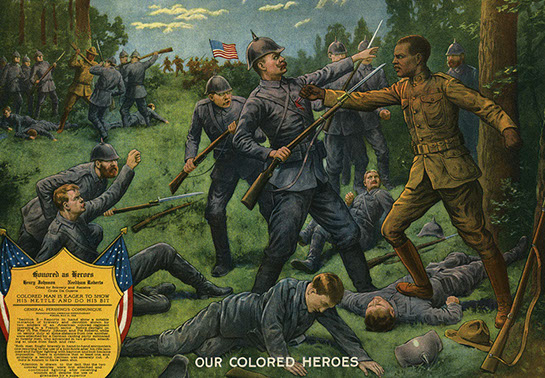

Battle of Henry Johnson

On the night of May 15, 1918, then-Privates Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts of the 369th Infantry Regiment were at a listening outpost in No Man’s Land to detect enemy movements. They were attacked by a German raiding party—estimated at between 20 and 30 soldiers. Roberts was quickly incapacitated, but he continued to hand grenades to a wounded Johnson. The Germans attempted to drag Roberts back to their trenches, but Johnson pursued them. Firing his rifle until it jammed and then using it as a club until it broke, Johnson drew a bolo knife and continued to fight. After reinforcements arrived, Johnson collapsed from 21 wounds.

“Our Colored Heroes”

This 1918 lithographic print was sold throughout the United States honoring Johnson and Roberts as heroes.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1976.31.10

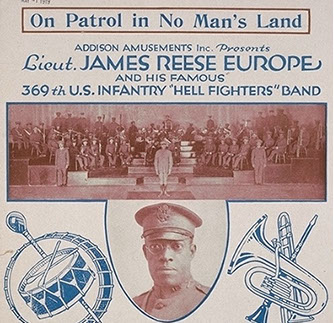

The Hellfighters Band

Colonel William Hayward raised $10,000 with which he tasked James Reese Europe with enlisting a regimental and befitting of the Harlem Regiment. In addition to Europe, the band of the 369th included renowned jazz artists Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake. Europe recruited talented musicians from New York City, Puerto Rico, and across the country. When the 15th New York—later reorganized as the 369th Infantry—arrived in France, they were almost immediately employed to play for both American soldiers and French citizens.

Introduction of Jazz to Europe

In February 1918, the band was ordered to travel to Aix-Les-Bains, France, a resort town in the southern Alps that had been converted to a respite area for the A.E.F. As the Hellfighters’ Band made the 400-mile trip, they played a series of concerts along the route in Nantes and Tours. For many French civilians, this was their first introduction to ragtime and jazz. In late August, the band played for a crowd of 50,000 in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris alongside some of the most renowned military bands of the Allied Armies to raucous applause.

Lieutenant James Reese Europe and

the Harlem Hellfighters Regimental Band

On board the transport ship in route to

New York City from France, 1919.

Courtesy of the National Archives

NURSES IN THE A.E.F.

By the time war was declared, the Army had 33 base hospitals nearly ready for service. Six sailed for France within a month. Each base hospital was staffed with a full complement of medical personnel, including 65 nurses. This number would quickly prove inadequate and was increased to 100 within six months.

By December 1918, 21,480 nurses had enlisted and more than 10,000 were in service overseas. This number was still inadequate to tend to the wounded—shipping was limited and nurses were given a lower priority over combat troops. During the war, over 200 nurses were killed. Many of these succumbed to the influenza epidemic of 1918 and other diseases contracted as they cared for the sick and injured.

American Nurses in Rouen, France, 1917

Courtesy of the National Archives

Recruitment

The U.S. Army coordinated with the American Red Cross to bolster its Nursing Corps and bring it to wartime strength under the newly formed Department of Military Relief.

“Five Thousand By June” (ca. 1917)

Artist: C. Rakeman

Printer: Rand McNally & Co., New York

Publisher: American Red Cross

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

Esther A. Denison, nurse

U.S. Army Nurses Corps

(1895–1993)

Denison grew up near Albany, New York and attended nursing school at Albany Hospital. When the United States entered the war, she enlisted in the U.S. Army Nurses Corps. After training at Fort Dix, New Jersey, she was assigned to a unit in Virginia in preparation for overseas service. Once in France, Denison was assigned to Base Hospital #41 just outside Paris.

“The first few weeks were very dramatic – we could hear the firing and battlefield casualties were coming in day and night.”

--Esther Denison, December 17, 1980

After the war, Esther Denison married Walter Haswell, of Colonie, New York, in a New York City wedding. The couple eventually moved to Syracuse and raised two sons. Esther worked at the Onondaga Pottery Company, Stickley Manufacturing Company, and Niagara Mohawk Power Corporation in Syracuse.

Passport Photo of Esther A. Denison

New York State Museum Collection, H-1979.95.11

Sheet Music, “On Patrol in No Man’s Land”

Lieutenant James Reese Europe composed this song in 1918 while recovering from a gas attack in France.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1978.206.1

NAVIGATE TO NEXT SECTION

|

|

Office of Cultural Education New York State Education Department Information: 518-474-5877 Contact Us | Image Requests | Terms of Use |