END OF THE WAR

THE END OF THE WAR: FEATURED SECTIONS

Drained of manpower and supplies, Germany signed an Armistice agreement with the Allies. The Armistice took effect at 11:00 a.m. on November 11, 1918 and ended the fighting in World War I.

Beginning in February 1919, the United States began the process of transporting two million troops back home from France. The warm reception these soldiers received was often in sharp contrast to the realities of returning to civilian life. New fears and problems pervaded. Many veterans faced unemployment and promised benefits were slow to materialize and often insufficient.

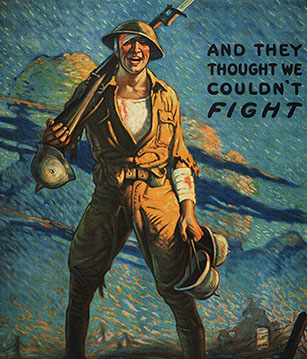

This poster celebrates the Allied victory following the Armistice. A wounded American soldier is shown carrying German helmets as war trophies.

“And They Thought We Couldn’t Fight” (1918)

Artist: Clyde Forsythe

Printer: Ketterlinus Print, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Publisher: Fifth Liberty Loan

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

With the German Army in retreat across the Western Front, the German government sued for peace. The Armistice that ended the fighting in World War I took effect on November 11, 1918, though the final peace would not be official until the Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919—after months of negotiations.

While President Wilson advocated a “Peace without Victors,” the Allies instead sought to punish Germany, who they blamed for starting the war. Kaiser Wilhelm II was forced to abdicate his throne in favor of a German Republic. Germany was prohibited from maintaining an army and was strapped with crippling reparations to the Allies totaling 132 billion Marks, or over $500 billion today. The Rhineland and Saar Valley in Germany were occupied by Allied forces.

The treaty also created the League of Nations, an organization designed to prevent future conflicts. The U.S. Senate, however, failed to ratify the treaty and the United States never became a member.

ARMISTICE

“Peace Hurrah”

New Yorkers celebrate news of the Armistice on November 11, 1918, in Manhattan.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

New York Times, November 11, 1918

The headline of the November 11, 1918, New York Times announced the signing of the Armistice.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

27th Division Cemetery

During the the Battle of the Hindeberg Line, the 27th suffered over 6,500 casualties, including 1,237 killed and 5,328 wounded. The Division’s losses for the entire war totaled 8,209. Many were laid to rest near the Hindenburg Line at what is today the Bony National Cemetery.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

HOMECOMING

As troop ships arrived in New York Harbor, the doughboys were welcomed by throngs of cheering citizens along the parade routes through the city. To celebrate the end of World War I, Mayor John Hylan ordered a “Victory Arch” constructed over Fifth Avenue at Madison Square to honor the City’s war dead. The temporary arch was designed by Thomas Hastings at a cost of $80,000 and was modeled after the Arch of Constantine in Rome, Italy. Tens of thousands of doughboys marched beneath the arch upon their return from the battlefields of France.

Arch of Freedom

This sketch of the “Victory Arch” was published by the Mayor’s Committee in order to solicit donations from the public for the construction of the Arch, eventually built on Fifth Avenue at Madison Square.

“Official Sketch of the Temporary Memorial Arch”

Artist: Chesley Bonestell

Printer: Alco-Gravure, Inc., New York, New York

Publisher: Rodman Wanamaker, Chairman, Mayor's Committee

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

Parade of Ships

The U.S. Navy’s battleship, U.S.S. Arizona leads the parade of nine battleships and their twenty-eight escort vessels during the Naval Review in New York Harbor on December 26, 1918.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

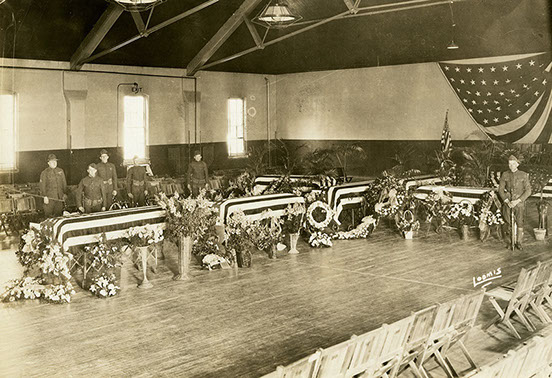

Coffins Laid Out in Elmira, New York

Not all homecomings were joyous affairs. This photograph shows a group of soldiers standing watch in a room full of coffins of New Yorkers killed in Europe in Elmira, New York.

Courtesy of the New York State Archives

369th Infantry Regiment

On February 17, 1919, one million New Yorkers gathered to welcome home the first of the state’s returning National Guardsmen—the 369th Infantry, Harlem’s Hellfighters. The 369th Infantry had seen 191 days of combat, more than any other American unit. Five hundred members of the regiment were awarded the French Croix de Guerre for gallantry, and the unit suffered 1,500 casualties. The regiment became the first to return to the U.S. from France after American commanders refused to allow the African American combat troops to march in the Allied victory parade in Paris.

Courtesy of the National Archives

AMERICAN LEGION

Following the Armistice, a group of American Army officers including Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. and Hamilton Fish, III of New York proposed the formation of a new veterans’ organization for former members of the A.E.F. After an initial meeting in Paris in March 1919, a larger congress was convened in St. Louis, Missouri, in May, The American Legion was formed at a founding convention in November in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Hamilton Fish III, formerly an officer of the 15th New York/369th Infantry, helped draft the preamble to the Legion’s constitution. The American Legion was to be a strictly non-partisan, fraternal organization that promoted issues central to the A.E.F. veterans, including permanent disability pay and soldiers’ bonuses.

"Americanism"

The Legion was a forceful advocate for 100% Americanism and anti-Bolshevism. In addition to forming a fraternal and advocacy group for returning soldiers, American Legion leaders saw the organization as a means to prevent radicalism from spreading within the ranks of the former A.E.F. veterans.

“Buddies”

Artist: Adolph Treidler

Printer: Carey Print Lith.

Publisher: American Legion

New York State Museum Collection, H-1976.149.3

Hamilton Fish III

1888–1991

Fish's family was long active and influential in New York State and national politics. Fish served as a white company commander with the African American 369th Infantry Regiment during the war. Following the war, he was elected to the House of Representatives in 1920, where he would serve for nearly 25 years. He was an ardent supporter of veterans’ causes and an early member of the American Legion. He spearheaded the effort to establish the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery. His experiences during the war led him to be an avid anti-communist and a staunch isolationist and he was a leading opponent of President Roosevelt and the New Deal. He died in Cold Spring, New York, at age 102.

Identity Card for Captain Hamilton Fish, A.E.F.

This card was used during his service in France with the Harlem Hellfighters.

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

DEMOBILIZATION

If the United States was ill equipped for war in 1917, it was even less prepared for peace in 1918. The administrative machinery that had been created to organize the war effort was quickly disbanded. No mechanism was established for the demobilization of millions of men now in military service, for the care of the wounded, or the difficulties of reintegrating these men into civilian life. Veterans’ bonuses and pensions were often insufficient and for those returning veterans unable to resume their civilian careers, little aid was available.

Veterans "Benefits"

The State Industrial Commission allocated $50,000 to open employment offices in cities around the state. Statewide, municipalities and charitable organizations attempted to aid in the re-employment of soldiers. Governor Alfred E. Smith appointed a Reconstruction Commission in March 1919 to replace the defunct Council of Defense, but most of the agencies under the commission ceased operations by December 1919. More than 930,000 American soldiers applied for some form of disability benefits by 1923. Of these, more than 200,000 were permanently disabled. New York State and the nation struggled to meet the need of these veterans.

Injured soldiers at Walter Reed Hospital, Washington D.C.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

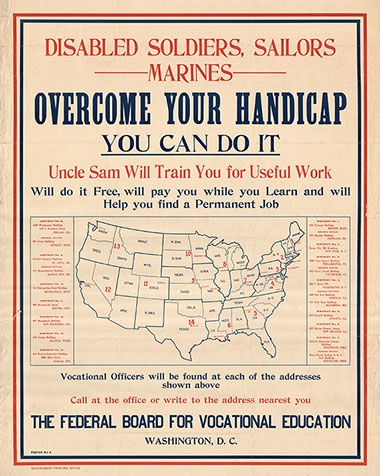

Rehabilitation

Much of the work of the Veterans Bureau focused on the rehabilitation and vocational training of disabled veterans was based on the Progressive ideal that the best way to “rehabilitate” these veterans was through job training and employment—as opposed to returning them as members of society that relied on a system of “public dependency.” Rehabilitation schools were established across the country, including several cities across New York State. While some veterans were indeed aided by this program—approximately 53 percent of those who applied received some form of rehabilitation training—many others were not. In 1919, New York State authorized $100,000 for vocational training of returning soldiers.

“Overcome Your Handicap”

This poster, published by the Federal Board for Vocational Education, offers wounded and disabled soldiers, sailors, and marines training in job skills to assist their return to civilian life.

Courtesy of the Rochester Historical Society

Re-Employment Bureau of New York City

As demobilization commenced, leaders in New York City feared a massive influx of soldiers would be discharged and saturate the employment market. Efforts were made to ensure that soldiers from inland communities and states were not discharged from military service in coastal port cities, but rather were returned to camps closer to their homes. New York City established a Re-Employment Bureau to assist returning soldiers and sailors in finding gainful employment. By September 1919, the Bureau employed 125 people and was placing an average of 1,000 veterans per week. Despite these efforts, unemployment among returning veterans remained high.

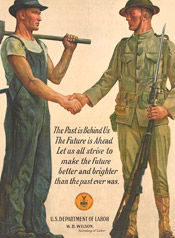

“After the Welcome Home— A Job”

Artist: E.M. Ashe

Printer: Heywood, Strasser & Voight Litho. Co., New York, New York

Publisher: U.S. Department of Labor Employment Service

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

SERGEANT HENRY JOHNSON

Johnson (1897-1929) was born in Alexandria, Virginia, and spent his early years in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. As a young man, he arrived in New York’s Capital Region where he became a redcap porter at Albany’s Union Station. Shortly after the United States entered World War I, he enlisted in the all-black 15th New York Infantry Regiment. His heroic actions while serving with the French Army in May 1918 left him severely wounded.

Despite being welcomed home as a hero, Henry Johnson was quickly forgotten by his nation. As a largely uneducated African-American veteran, Johnson was unable to take advantage of the few programs available to wounded veterans. He advocated for veterans’ benefits and lobbied unsuccessfully with the New York State Legislature for a bill that would have given World War I veterans preference in civil service hiring. His outspokenness after the war about racism in the A.E.F., however, likely alienated him from erstwhile white supporters.

After the war, Johnson returned to civilian life as a porter, but his wounds were too painful. The scars of war led to an estrangement between Johnson and his wife, Edna. He died on July 10, 1929, at the age of 32. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Henry Johnson, ca. 1919

Courtesy of the U.S. Army Center for Military History

77th Division in New York City on May 6, 1919

Courtesy of National Archives

ARTIFACTS

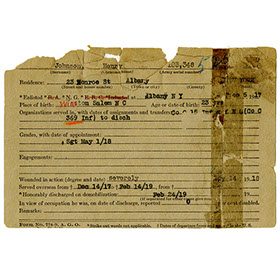

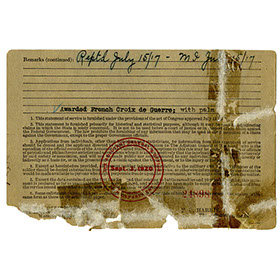

WWI Service Card for Henry Johnson (front)

WWI Service Card for Henry Johnson (back)

Croix de Guerre

This Croix de Guerre is similar to the one that was awarded to Henry Johnson in 1918. The bronze star device shown here would have been replaced by a bronze palm to denote the award was presented for Johnson’s heroic actions on May 14–15. He was the first American and one of nearly 500 “Hellfighters” to receive the honor. Johnson did not receive similar recognition in his own country. It was not until 1996 that Henry Johnson was awarded the Purple Heart. In 2003, the U.S. Army awarded him the Distinguished Service Cross. On June 2, 2015, Henry Johnson was finally awarded the Medal of Honor.

New York State Museum Collection, H-2012.23.8

NAVIGATE TO NEXT SECTION

|

|

Office of Cultural Education New York State Education Department Information: 518-474-5877 Contact Us | Image Requests | Terms of Use |