AMERICAN ENTRY

At President Wilson’s urging, citing Germany’s use of unrestricted submarine warfare as a pretense, Congress declared war on April 6, 1917. The United States was completely unprepared for a global war. The U.S. Army numbered only 200,000 soldiers and the weapons, ammunition, and materiel needed to fight a modern war were in short supply. Before America could impact this “war to end all wars,” the nation needed to mobilize on an unprecedented scale, and looked to expand its armed forces to four million.

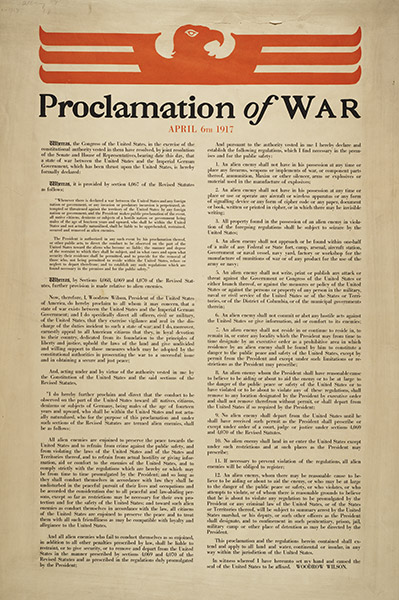

Proclamation of War

In leading the nation into “the most terrible and disastrous of all wars,” President Wilson asserted that the United States was fighting to “make the world itself at last free.”

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

AMERICAN ENTRY: FEATURED SECTIONS

Americans were urged to rally to the defense of the Allied Cause against the “Barbarous Huns.” President Woodrow Wilson and others portrayed the conflict as a defense of civilization and a war to save democracy.

“Civilization Calls” (1917)

Artist: James Montgomery Flagg

Printer: Hegeman Print, New York, New York

Publisher: Mayor’s Committee (Wake Up America Day)

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

Unlike previous conflicts in American history, the U.S. Army did not seek to utilize volunteer regiments raised by individual states in order to increase the size of its military force. Following Congress’ declaration of war, the federal government worked to establish a Selective Service Plan in order to meet the nation’s manpower needs for the World War. As a result, relatively few enlistments were recorded for April and May of 1917. Thousands of New Yorkers volunteered for service with the state’s National Guard as it was brought up to wartime strength for federal service. Millions more registered for the draft when the new Selective Service Plan was enacted in May.

A CALL TO ARMS

Private T. P. Loughlin of the 69th Regiment, New York National Guard, (165th Infantry) bidding his family farewell.

Courtesy of the National Archives

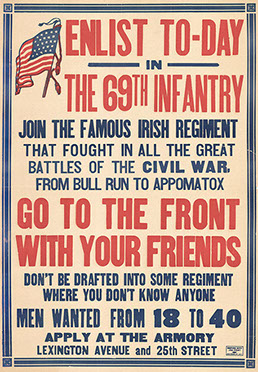

69th Regiment

Organized in New York City in the 1850s—having served throughout the U.S. Civil War—the 69th Regiment was composed of Irish-Americans and earned the nickname “The Fighting Irish.” When brought to wartime strength, the regiment’s composition went from 85 percent Irish to 50 percent. The regiment’s chaplain, Father Francis Duffy, stated that the men of the 69th were, “Irish by adoption, Irish by association, or Irish by conviction.”

69th New York Recruiting Poster

Artist: Unknown

Printer: Empire City Job Print

Publisher: New York National Guard

New York State Museum Collection, H-1984.78.1

15th Regiment New York Guard

Harlem’s 15th New York was the first regiment in the state to reach wartime strength. Racial tensions in both South Carolina and Camp Whitman on Long Island prompted the movement of the regiment to France. Thus, the 15th was the first New York unit to arrive overseas.

Recruits Wanted, 15th Regiment New York Guard

Artist: Unknown

Printer: Unknown

Publisher: New York National Guard

New York State Museum Collection, H-1975.185.4

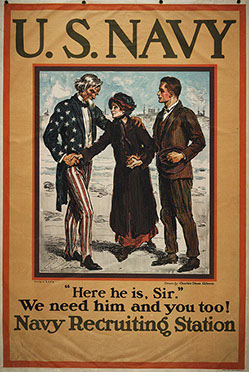

New Yorkers in the Navy

More than 25,413 New Yorkers served in the United States Navy during the war with an additional 48,068 men and 2,329 women serving in the Naval Reserve.

“Here he is, Sir” (ca. 1917)

Artist: Charles Dana Gibson

Printer: Latham Litho. & Ptg. Co., Brooklyn, New York

Publisher: United States Navy

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

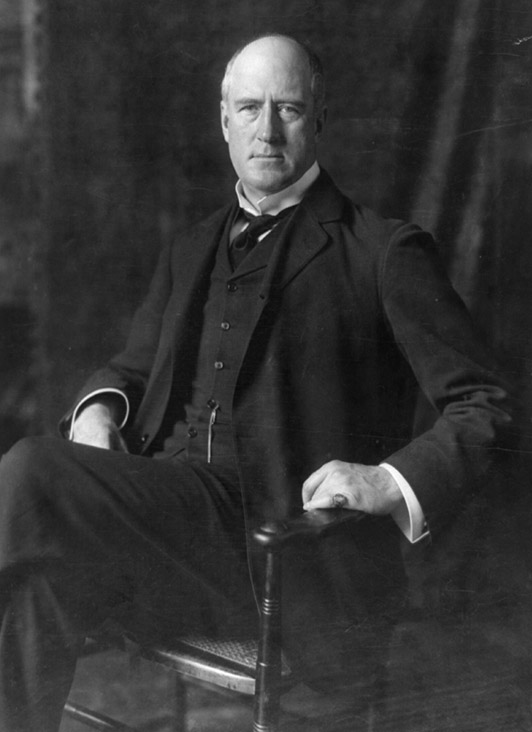

Charles Dana Gibson (1867–1944)

Gibson was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts. As a young man he exhibited significant artistic talent and was enrolled in the Art Students League in New York City. Gibson remained in New York where he found work as an illustrator for publications including Life magazine, Harper’s Weekly, and Collier’s. He is perhaps most famous for his “Gibson Girls” drawings that helped “define” beauty in American advertising until well after World War I. During the war, Gibson, who was the president of the Society of Illustrators, headed the Division of Pictorial Publicity.

Charles Dana Gibson ca. 1914

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

THE DRAFT

On May 18, 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act authorizing the President to increase the size of the United States military via a draft. The draft initially called for men between the ages of 21 and 31. By September 1918, the age range was expanded to 18 to 45.

At the beginning of the war the U.S. Army numbered only 200,000. By 1918, 2.8 million men had been drafted into service. The draft was suspended following the Armistice in November 1918.

Elmira Draft

A group of men stand outside the draft headquarters in Elmira, New York reviewing the list of local men drafted into military service.

New York State Archives

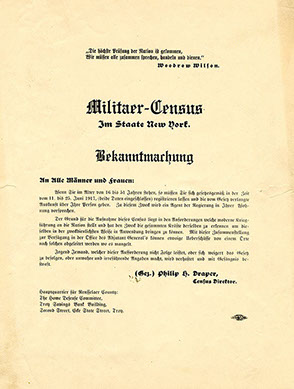

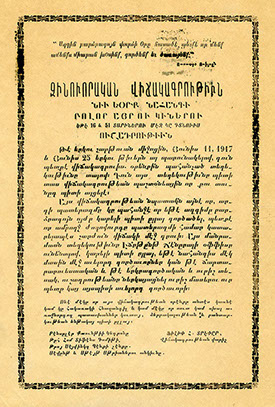

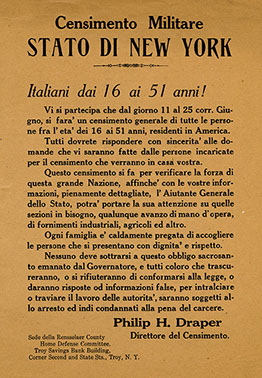

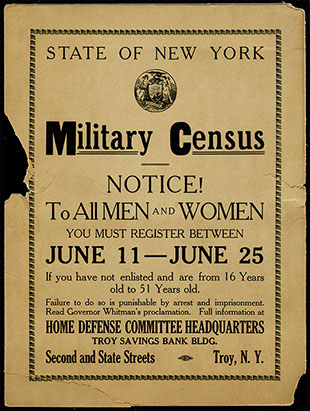

Military Census

The State Legislature on March 29, 1917 authorized Governor Whitman to carry out a census, requiring the registration of all men and women between the ages of 16 and 50. When Congress enacted the Selective Service System 2,917,909 names of New York men were forwarded to Washington.

New York State Archives

Foreign Language Broadsides for the Military Census

Broadsides for the State’s military census were printed in numerous languages including German, Armenian, and Italian. New York State Archives

Armband

This armband was given to drafted men before they were inducted into the Army and issued uniforms.

New York State Museum Collection, H-1987.1.23

Service Flag

This service flag hung in the Staten Island home of Peter Schaming, who served in the 106th Infantry Regiment, 27th Division, American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.). Service flags, like this one, indicated that a household had a loved one in military service. The blue stars on the white field corresponded to the number of family members on active duty. A gold star denoted a serviceman or woman who had been killed in service to the nation.

New York State Museum Collection, H-2007.7.1

CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS

Many religious groups were exempt from military service under the Selective Service Act if they served in a noncombatant role. Others refused to fight based on political or social viewpoints. About 2,000 absolutist conscientious objectors refused to accept service as noncombatants, citing their belief that doing so would indirectly aid the war effort that they opposed. Some eventually accepted farm furloughs or other substitute service. Many others remained imprisoned until well after the Armistice in November 1918. Many were subjected to harsh treatment, verbal, and physical abuse, before being transferred to Fort Riley and other military camps across the nation.

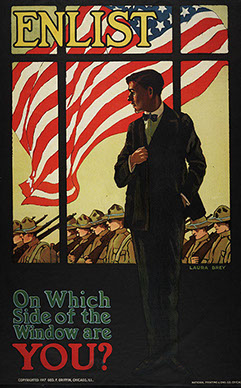

Which Side?

Men who refused to join the army were seen as shadowy lurkers, hiding from their duty to the nation. Conscientious objectors and other “slackers” who refused to fight were treated very harshly by the U.S. criminal justice system, often receiving extended sentences at hard labor in U.S. military prisons.

“On Which Side of the Window are You?” (1917)

Artist: Laura Brey

Printer: National Printing & Eng. Co., Chicago, Illinois

Publisher: George F. Griffin, Chicago, Illinois

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

Howard W. Moore (1889-1993)

Born in Sing Sing (now Ossining), New York, Moore grew up in Cherry Valley, New York. At age 14 he moved to New York City, where he landed a job with the New York Telephone Company. In 1917, he began attending lectures at the Rand School, headquarters of the Socialist Party in Manhattan. While he sympathized with many of the socialists’ tenets, Moore never became an active member. He also frequently attended sermons by Rabbi Stephen Wise and Unitarian minister John Haynes Holmes. It was at this time that Moore first developed pacifist leanings.

Witnessing the pro-war propaganda in New York City, and the backlash against any who opposed it, led Howard W. Moore to declare himself a conscientious objector.

“[I am not a member of] any religious sect or organization whose creed forbids me to participate in war, but the convictions of my own conscience as an expression of my social principles forbid me from so doing and [thus, I] claim the same rights accorded under the law to members of a well-recognized religious sect or organization whose principles forbid their members to take part in war.”

--Howard W. Moore, Affidavit to Local Draft Board, December 28, 1917

Despite harsh treatment and imprisonment, Moore remained resolute in his refusal to serve. He was imprisoned for over three years at military posts across the country. Following his release in 1920, Moore returned to New York, eventually settling on the family farm in Cherry Valley.

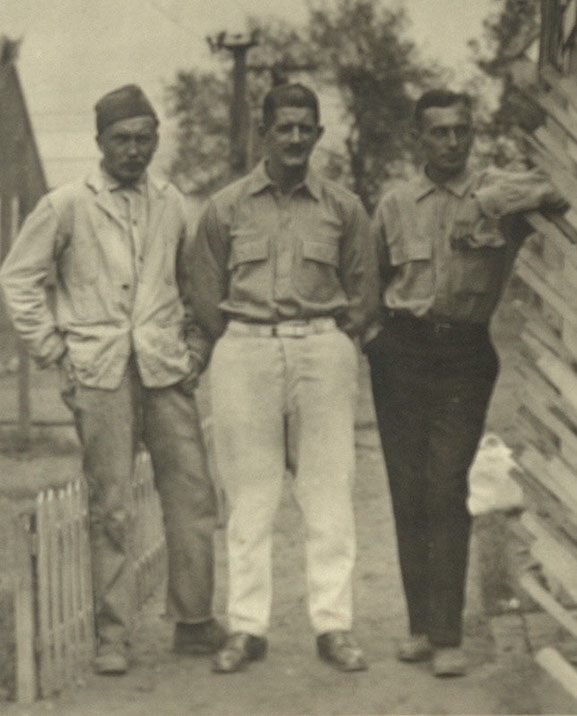

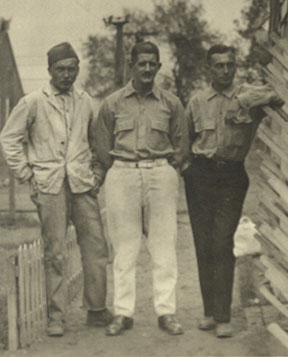

Howard W. Moore (far right) and fellow conscientious objectors at the detention camp at Fort Douglas, Utah in 1919.

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

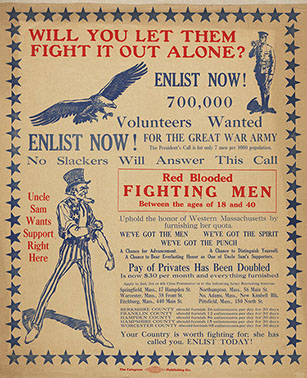

Slackerism

The American Protective League and other groups were instrumental in assisting the federal government to develop extensive lists of “slackers.” The term was commonly used throughout the war to describe any individual who avoided military service or refused to support the war effort. “Slacker Raids” rounded up any men in a given area suspected of being of military age. On September 14, 1918, more than 60,000 men were detained in New York City during one of the largest slacker raids. Fewer than 500 of these men proved to be actually evading the draft.

In this photograph, a U.S. soldier inspects the paperwork of a passing civilian to ensure he has enrolled for the draft. Slacker raids and other measures were implemented throughout New York State and the nation to compel compliance with the Selective Service Act.

From U.S. Official Pictures of the Great War (Washington, DC: Pictorial Bureau, 1920), New York State Museum Collection, H-1971.113.11

Men who refused to enlist in the military were labeled the derogatory term “slacker.”

“Will You Let Them Fight it Out Alone”

Artist: Unknown

Printer: The Telegram Publishing Co., Holyoke, Massachusetts

Publisher: U.S. Army Recruiting

New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections

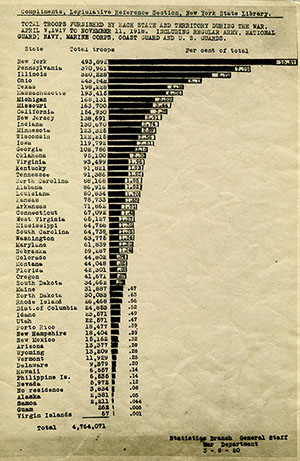

NEW YORKERS IN AMERICAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCE

New York State contributed approximately 500,000 of its citizens to military service, serving in all branches of service. This accounted for more than ten percent of military service during the war and was the largest contribution of men from any state in the nation. Additionally, an unknown number enlisted with the Canadian or British forces prior to American entry into the war.

Total Troops Furnished by Each State and Territory during the War

New York State Archives

ARTIFACTS

PAINTED HELMET:

27th "Empire Division"

SHOULDER SLEEVE INSIGNIA

369th Infantry Regiment

PAINTED HELMET:

78th Division

SHOULDER SLEEVE INSIGNIA

165th Regiment, 42nd "Rainbow" Division

PAINTED HELMET:

77th “Liberty” Division

COLLAR INSIGNIA

U.S. Army Nurses Corps

All Aboard!

U.S. Marines wave from the windows of a train of the Pennsylvania Railroad bound for the New York Port of Embarkation.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

PORT OF EMBARKATION

The New York Port of Embarkation (NYPOE) was established as a distinct Army Command during World War I to facilitate the transport of troops and war materiel from the Port of New York to overseas service. NYPOE oversaw three transient camps for troops on Long Island to house thousands of soldiers on their way to Europe. The NYPOE was also in command of sub-ports at Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia.

By the end of the war, New York City surpassed all others as the world’s busiest seaport. It would remain so for the next forty years. Because of its vital role in shipping men and supplies to Europe in World War I, New York Harbor became a distinct Army Command and would play a crucial role in the Second World War.

Transport

Transports sail past the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor carrying troops and supplies bound for France.

Courtesy of the U.S. Army Center of Military History

NAVIGATE TO NEXT SECTION

|

|

Office of Cultural Education New York State Education Department Information: 518-474-5877 Contact Us | Image Requests | Terms of Use |